This book has very little in the way of a plot. I know the back cover promises a plot, but the back cover is probably more suspenseful and interesting than the book itself.

This book has very little in the way of a plot. I know the back cover promises a plot, but the back cover is probably more suspenseful and interesting than the book itself.

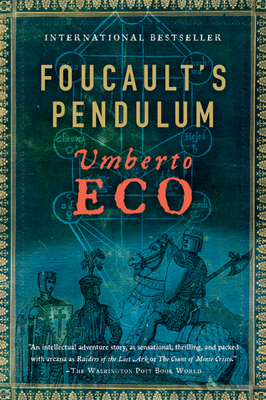

That said, there’s the possibility of an intriguing theme and a satirical commentary on the kinds of people who think the Templars, the Masons, or the Federal Reserve have superior organizational powers that prevent them from being as haphazardly-run as say, my local school board, your DMV, or any large organization ever. Beyond that, it’s a lot of words, most of which appear to just be the author trying to prove he’s a smarty pants. (I also have a personal suspicion that because The Name of the Rose was well liked and they could put Templar Knights on the cover of this one, it maybe wasn’t edited as tightly as it should have been, but maybe that’s just me.)

(There may be a spoiler or two below, but if you’re one of those people who isn’t @steveweddle and just bought the book but never finished it, now you can pretend.)

All that said, there were some parts I liked, chiefly the way Lia calls the narrator on his BS. Others:

- At some point in chapter 37, Belbo attempts to describe the change that overcame the intellectuals of his day, who found themselves trading their revolutionary ideals for shallow commercialism and it’s quite good. It’s too bad many readers won’t likely get that far, because it does serve to add a layer of interest to both Belbo and Casaubon.

- Before Lia tells him, in way more words, that he’s an idiot, Casaubon himself starts to realize that when you put too much emphasis on numerology and legends, you can start to see patterns that only exist in your own mind. (This occurs in chapter 63.)

- A few pages later in chapter 64, there’s this (that reminded me of how it feels to work with the loony and the criminal, but maybe also why writers need community and companionship): “Among the Diabolicals, I moved with the ease of a psychiatrist who becomes fond of his patients, enjoying the balmy breezes that waft from the ancient park of his private clinic. After a while he begins to write pages on delirium, then pages of delirium, unaware that his sick people have seduced him. He thinks he has become an artist. And so the idea of the Plan was born.”

- Just before chapter 96, he begins to rant “if they strip you of your possessions, raise your sons to be merchants…if they threaten your lives, raise your sons to be physicians and pharmacists…” By this point, I think I was mostly hoping Umberto Eco would shut up — never good when you start to think about the author while reading a novel — but it reminded me of the John Adams quote. (“I must study politics and war, that my sons may have the liberty to study mathematics and philosophy, natural history and naval architecture, in order to give their children a right to study painting, poetry, music, architecture, tapestry, and porcelain.”) So, perhaps I’ve maybe read too much, too.

- Perhaps the best defense of the “trashy genres” I’ve read in a while (in chapter 97): “Proust was right: life is represented better by bad music than by a Misa solemnis. Great Art makes fun of us as it comforts us, because it shows us the world as the artists would like the world to be. The dime novel, however, pretends to be a joke, but then it shows us as the world actually is — or at least the world as it will become.”

And so with that, I will go back to my stack of crime fiction novels waiting to be read.