As originally published on Medium.

I joked in a tweet that I am not a writer because if I could intern or apprentice with anyone, learn their craft and how they do it firsthand, it would be with photographer Clyde Butcher. He still uses large format cameras and shoots on huge pieces of film that can be printed in black and white in his studio. He lugs them out into the wilderness, most often the wilds of Florida, and captures the beauty of nature in a way similar to Ansel Adams. His images are so magical I can stand before them taking in the talent, the chemistry, the artistry until every other member of my party has grown bored and wandered off.

Of course, when I say I’d love to apprentice with him, this is in some idealized fantasy world where Covid doesn’t exist, where I have the time and monetary freedom to do such a thing, and he is younger and more willing to take on a student.

It’s still telling on myself.

In one of my early writing experiments, I drafted a play or musical of sorts using songs I’d recorded from the radio. (I’m old so when I was seven or eight that was the only way to go about having a group of songs in a particular order was to sit before the radio, finger at the ready to push record, and hope the DJ didn’t talk over the intro or outro. Unless, of course, you owned one of the fancy tape players with more than one deck — and the disposable income to buy all those singles or albums. Eventually, I’d get my hands on a triple-deck tape player that was the closet I would come to a 5-disc changer for another decade, but that might have been after I’d passed the age when I shared my work with others, unashamed and excited.)

Maya Angelou’s famous quote about creativity is part of an article in which she goes on to talk about how “[i]t is our shame and our loss when we discourage people from being creative…Too often creativity is smothered rather than nurtured. There has to be a climate in which new ways of thinking, perceiving, questioning are encouraged. People also have to feel they are needed.” This was in 1982. A year or so later, my parents still hadn’t gotten the memo as they responded to my melodramatic and derivative “play” with boredom and the sort of looks that might get you your own shrink if you were from the kind of family that did that sort of thing. I got the immediate and distinct impression that there was nothing good in my efforts and that they were unwelcome and strange.

I think the next time I showed anyone something I’d written (unless I had to for a grade) was in my thirties. And even then, I think most agents probably had a similar reaction as my parents. They just had it in their homes and offices instead of my grandmother’s living room, that thinking back was a perfect encapsulation of her aesthetic and life. Perhaps my parents were onto something back then. Or perhaps my writing might have improved a bit faster if I hadn’t been so ashamed of it that I hid notebooks of it behind shoeboxes, under the bed, and in the space between the drawer and the back of the dresser.

Stories of children who took diaries and notebooks of stories to school with them always boggled my mind even before other students or teachers found them and embarrassed or questioned the intentions of the writers. How anyone could risk another soul seeing the thoughts in their heads baffled me even as I mimicked soap operas I caught in the summer time and rewrote episodes of Facts of Life with kids I knew so they seemed more realistic.

My husband’s creative endeavors during those ages tended to lean more toward movie making and he tells of filming such epics as The Moped Warrior with a video camera and editing the VHS with a pair of daisy-chained players with his friends. I’m not sure I could say his parents were much more supportive except for letting him use their technology and not suggesting he needed a psychiatrist to examine him.

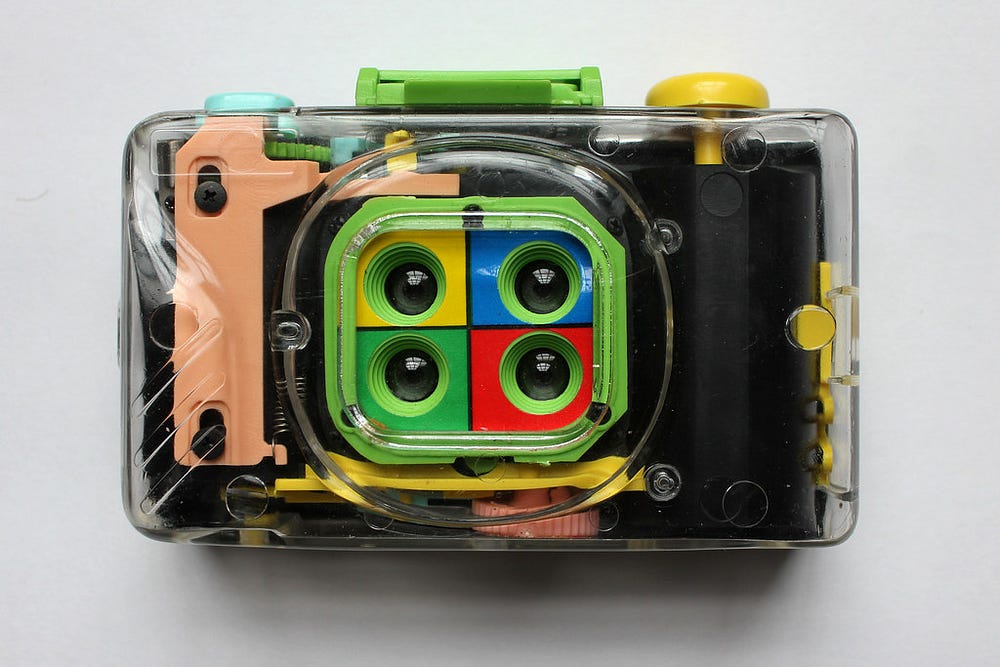

Then again, cameras were something even my parents understood. At the time I was learning to hide my words, I was encouraged to share my pictures. Back then, my colorful plastic 110 cameras were mostly for end-of-year field trips, birthdays, and other special occasions when you wanted to remember the day with blurry images of people you’d later forget.

Seriously, for all the modern attraction with Lomography and plastic cameras, there’s a reason people revived the Diana and Holga, but not the 110. (To be fair, they did revive it in black and white in 2012, but that was pretty much after they’d dug through the photographic graveyard and reanimated everything but the daguerreotype.) Nothing at a distance was in focus. Nothing up close was in focus. And the film itself was so small, even 3.5 x 5 pictures were a grainy mess. The 110, which was generally slightly longer than an Android phone and about six times as thick, made it impossible to believe in tiny spy cameras being useful. Taking a picture on film smaller than the 110 sounded like a great way to keep something secret forever. (Although I fully admit to having one of these things in all black and loving it despite it not being practical or ever working as advertised.)

For those who have never had the pleasure of using 110 film, it came in a cartridge so it was super-easy for kids to use. Back then we knew recycling was important, but we didn’t quite understand that adults were lying to us about how recycling worked or that it was far more important for companies to make less plastic than to leave it up to us kids to figure out what to do with it. It was shorter than 35mm and generally cheaper. It was also, again, utter crap.

In 1984, though, I got the best gift for a budding photographer, only to lose it the following year in a lawsuit.

The Kodak CHAMP instant camera was awesome, took the kind of dreamy, randomly-sharp pictures that would later be all the rage for Lomography fans and would initially inspire a raft of filters and apps in the early days of Instagram decades later. Not only were they instant in an era where most cameras required you to finish the roll, save up your allowance or lunch money, and talk someone into taking you to the drug store to drop it off, wait a week, and then get a ride to pick up the photos, but the film itself was the perfect hybrid of the older peel-open Polaroid film and the newer “shake it” (but, really, please don’t) style. Because Kodak had been making Polaroid’s film stock for ages, they were kind of perfectly poised to take the good parts of both styles, creating a film that instantly began to develop once ejected without any messy chemical sheets to dispose of, but had a back that could be peeled off later so the photos sat flat in albums.

I loved them. I loved running around with that lunchbox-sized hunk of plastic shooting pictures of everything I could find. And because I didn’t have to wait to see the results of my experiments, I could adjust my composition or technique on the fly. (I could also take photos of my Barbies wearing the clothes I’d designed out of scraps and staple them to the sketches, but that’s a whole other dumb thing child-me did.)

Picture-taking me was something my parents understood. They took pictures. Everyone they knew took pictures. Maybe not close-ups of mushrooms or strange angles of canoe parts, but I guess they assumed I’d eventually settle into taking pictures of friends like a normal kid if I ever made any. To that end, they indulged my weirdness. They supplied film, drove me to the local Eckerd Drugs to get film developed, and let me use the heavy Vivitar SLR with removable lenses that I still have somewhere in the house along with my old Minolta SLR, Canon SLR, and collection of Polaroid Land Cameras purchased long after their heyday when I had to rewire the battery compartment to accept AAAs.

I run across those occasionally and wonder if I can still find the magic I felt using those thirteen years ago. I still have 120 film (far bigger film than the 110 despite what the names suggest) I never developed even though I have a negative scanner still sitting on the end of my desk.

And I still have the photographs my mother hung on her walls until she died. Surprisingly, they were mostly landscapes, black-and-white images of farm equipment or flowerpots rather than people. Seems the images I gifted her over the years became décor as much so as the pictures of her mother and granddaughter hanging near the dining table.

Many of those were printed when I was in college. Even though I’d gotten good grades and comments in Honors English, when I decided to be an impractical freshmen and switch my major from International Business to Art, it was so I could take photography rather than writing. For the record, I was not a particularly-gifted photography student and our professor, who shaved her head in the dead of winter on what was rumored to be a party dare, did her best to discourage me back into any other college on campus. (The 2D design professor also tried mightily to ensure I knew I was awful.)

I did eventually end up with a degree in business after transferring to the Art Institute in Fort Lauderdale and realizing that paying an obscene amount of money to take pictures of soap and cat food in a studio was beyond foolhardy. ADHD and being too mature in middle- and high-school can lead to some dumb decisions in one’s twenties, but that’s a topic for another day.

So, maybe I’m not really a photographer after all. Maybe that was just a multi-decade fever dream caused my the chemicals we used to use to make photographs.

I still “see” in images, whether abstract paintings and designs as I drift off to sleep or the snapshots frozen before my face as I hike and roam city streets. When I used to write, I still “saw” in images, though now I feel blocked and the images won’t play right, as though the video files in my brain are all corrupted, mislabeled, or in the wrong format.

Recently, (as though time still has meaning), Amanda Gorman was interviewed by Anderson Cooper following her brilliant inauguration poem. He asked her if she was inspired by images from the Capitol insurrection and she corrected him. “I’m a poet,” she said, “so I often I don’t work in images. I work in words and texts. And so, what I was actually doing is while keeping mental sanity looking through the tweets and the messages and articles and seeing what stood out.”

Her words stuck with me long after that interview, and it was likely the words no one else paid much attention to, the words describing her craft and how she makes sense of the world. Her words made me question if I’ve ever been a writer. Can one be a writer if they are primarily trying to find the thousand words to describe the photograph they imagine, but can’t shoot.

I don’t really have an answer to that question anymore than I have any idea how to repair those old Land Cameras that stopped working.

I do hope to find a way to continue doing both, to keep experimenting with words and pictures, no matter how terrible I am at either (or both).